The Argument I Won

Until I didn’t

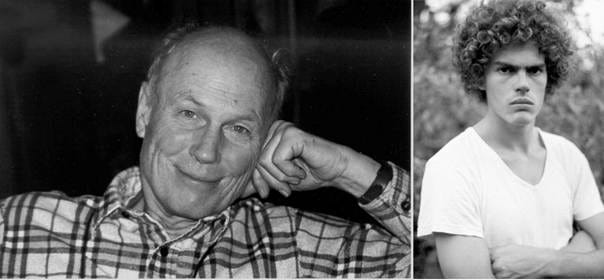

My dad and I had a rather difficult relationship for most of my life. Had I not left home seven days after I (barely) graduated high school, one of us was likely going to visit the morgue, either to view, or be viewed. Which one of us that would be, was up for grabs.

We were quite different. Dad was serious and brilliant; me, not so much. Dad never completed high school (I barely completed high school). He took a statewide test in Ohio and scored either one or two in the entire state. He was then removed from high school and placed in college at Miami of Ohio, where my grandfather taught the romance languages as head of Miami’s language department, to study physics.

This has nothing to do with the rest of the story, but dad had a famous nose. Until he was put into college, dad played football in high school under the coaching of Weeb Ewbank. When dad broke his nose in a game, Weeb relocated it back into place but from then on it had a slight crook in it. Weeb went on to coach the Indianapolis Colts with Johnny Unitas to an NFL championship and then moved to the NY Jets, where he signed Joe Nameth and went on to win the Super Bowl.

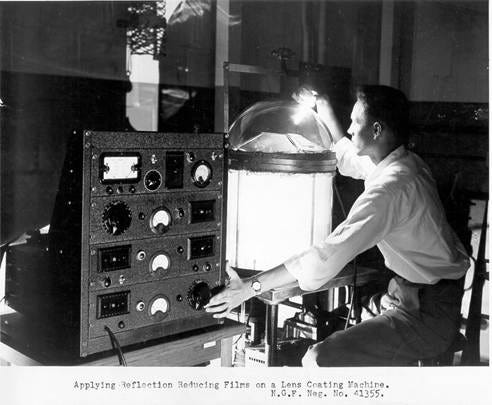

Dad finished his PhD in physics at the University of Colorado and was hired as a physicist at Bell Laboratories in Murray Hill, New Jersey. He worked primarily with the creation of semiconductor devices. He invented the 8-watt diode, the gallium arsenide chip and created the Irvin Curves. The Irvin Curves are some sort of computational something or other, having something to do with the diffusion profile (either erfc or Gaussian), type (n or p), and background doping concentration (Nc). If you actually understand any of that you can go to Irvin.net and calculate exact values for the average conductivity. The Irvin Curves are still used today.

Me, I have no idea what any of that means. Personally, I think my father just made up a couple big, sciency words that sounded incomprehensible and all very smarty-pantsy. I’m guessing that all the other scientists said, “Yeah, that sounds good to me, go with that.”

Dad very rarely spoke about his work, (primarily because no one could understand it) but one evening when I was small, dad came home from work and showed me a very tiny oddly shaped gold thing-a-majig and said, “This is what I do at work. It is covered in pure gold (which impressed me, we were obviously very rich now!), and it is going in a device called Tellstar, (which didn’t impress me; what in hell was Telstar?) which will go up into space (and I was back to being impressed). Telstar, our first satellite, still orbits the earth so, I guess it was dad’s way of still keeping tabs on things.

My favorite dad story is: When my father was a small child, my grandfather and grandmother had several professors from the university over after classes for coffee and cake. My grandfather brought up a difficult math problem to the group that he had spoken about with another professor earlier in the day, but neither had solved it. He hoped the group could come up with the answer. No, I don’t remember what the problem was. (I don’t math much, I drawr pitchurs fer a livin’), but suffice it to say, it was a difficult one and it was stumping the professors. The problem was being discussed in the living room everyone giving their take on it but no one solving it.

My father who was six or seven at the time was playing in the hallway and called out to get my grandfather’s attention from the door of the living room and my grandfather said, “Not now, John. We’re busy. I’ll talk with you later.” The coffee and cake continued to be consumed, and the problem went on being debated. A while later my dad tried to interrupt again, and was again asked to wait. Dad continued to listen to the discussion waiting for it to be over, but finally ran out of patience and yelled, “I know the answer.”

The room stopped. My grandfather said, a bit impatiently, “What do you want, John?” My father said, “I know the answer.” My grandfather asked, “What answer?” Dad said, “to the problem you are talking about.” Everyone looked at one another and after a rather long beat, someone asked, “What is the answer, John?” I imagine they expected a cute, humorous, only-a-child-could-say-it type of answer.

My father supplied his answer, which proved to be correct. Needless to say, the professors were duly impressed.

I was told that story by my grandfather when I was in my late twenties or early thirties. Up until then my dad was simply an impediment to my happiness. But hearing that story I finally realized that my dad’s brain was different and probably better than most brains and certainly far better than my brain.

Unfortunately, for a very large part of my life, my brain and my dad’s brain did not get along very well.

One very irritating aspect of living with my father was that winning an argument was flatly impossible. Not only did dad have a streak of devil’s advocate in him, but no matter how well you defended your position, he would take it apart piece by piece with facts, numbers, positions, statistics, or his goddamn slide rule, to remove any doubt that you had A) no clue what you were talking about and/or B) any business existing as a living organism. Shutting up was usually the best way to avoid further humiliation.

If you couldn’t discuss the ins and outs of string theory or quantum mechanics by the time you were 10 or 11, he assumed there was little hope for you, and you would eventually be forced into a low paying career as a doorstop somewhere. Due to this we avoided each other for the better part of 35 years.

Dad was not one to hand out atta-boys or compliments. Doing a job well was your reward, not getting praised for it. He did not like big, loud, pushy talkers who made jokes about everything and didn’t do their homework. This was another area that grated on each other’s nerves. Because I was a big, loud, pushy talker who made jokes about everything and never did his homework.

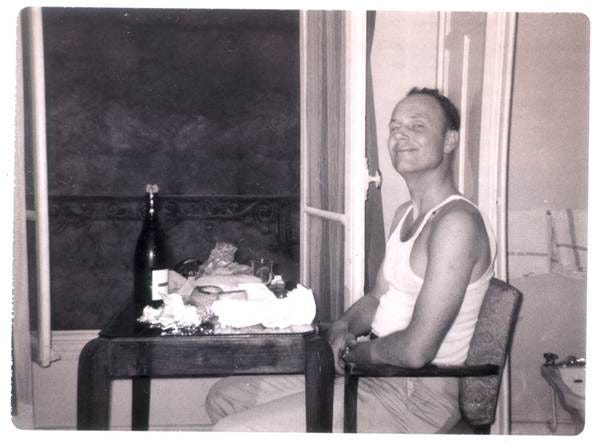

Dad did not joke, or rather, if he had enough wine he had one joke.

Here is how it goes: Never drink while driving, you might spill some. He found that hilarious.

But dad did compliment me one time. I was at home visiting, and dad had one of physicisty sciencey type friends over who had wandered about the house looking at the artwork hung on the walls (My mother hung all the crap I had drawn since the 2nd grade) and he said to my father, “John, I had no idea your son was an artist.” My dad replied, “Yes … we’re just glad he can do something.” Now some of you may think that was not really a compliment, but I assure you it was. I can’t tell you how proud I was at that moment. It was official, I could do something! That, my friends was big praise from Mr. Physicist.

Anyhoo, life went on, Dad and I finally found a way to get along in my late thirties by not talking. I still hadn’t won any arguments, but we could work on projects without killing each other. If we were putting down a floor or plumbing a laundry room, sheet rocking a wall, or building a deck we could get along without killing each other. By keeping the talking to a minimum I didn’t have to hear him call me mentally deficient and he didn’t have to hear me cuss him out. And we even managed to laugh at an occasional mistake we had made.

Here is one we laughed at: Dad saved and reused everything. We had hundreds of recycled bottles of various fluids and chemicals around the house for his various experiments, developing photographs, or his wine making. One day, while working to put a huge cast iron stove in the living area, he grabbed his beer and took a swig (dad liked a beer while working). There were actually two beer bottles there, and the beer bottle he grabbed happened to be one he had recycled to store trichloroethylene in. Tri-clor is a powerful solvent that we kept around for cleaning anything you needed to dissolve. Dad lurched forward, blew a classic spit-take of tri-clor all over the wall, and choked out a “goddamn that tastes awful!”, singlehandedly creating the “Day dad drank the trichloroethylene” story, which my brother and I enjoy telling to this day.

Years later dad ended up with prostate cancer, which most likely was caused by drinking trichloroethylene out of unmarked containers thinking it was beer. Sometime before he died, I was visiting and we were discussing politics and the state of the country. This took place during the imbecilic Bush years which now seem wonderful by comparison. Dad was a liberal democrat and knew his politics inside and out, and I was very careful to get my facts right during the discussion. Part way through the discussion dad paused and said, “The United States will become a 3rd world country in a relatively short time.” I was very surprised. That did not sound like dad. I pushed back, saying that our constitution, the separation of powers, the laws that govern us, etc., etc., etc., may take a beating from time to time due to the stupid, power hungry republicans, but I argued that the sheer inertia of our country, its many systems and laws, both state and federal, would hold and get us through the times when lesser men tried to tear things apart. The ship would right itself.

Dad thought about it and said, “Well, you read more about those things than I do now, so maybe you’re right.” And we went on to talk of other things (shoes and ships and sealing wax and cabbages and kings).

That was a high mark for me. Not only had dad respected my argument, but felt I was right. I had won my first, and only, argument with dad.

But it didn’t hold. Prophetically he knew that we would end up with a cabbage for a king.

From time to time I have brought up that conversation, telling people, “I did win one argument with my father.” I should have waited longer for that pronouncement. Back from the dead, dad foresaw something the rest of us didn’t. Like the university professors in my grandfather’s living room pondering a problem and getting nowhere, dad listened, mulled the problem over, and gave them the correct answer.

Over 20 years ago he looked into the politics of the future, saw a problem and knew a reckoning was coming.

So, the score still is: Dad 11,679 | Me 0

I think he gave me that win to be kind. We had our differences, but I gotta give the man credit. He was a very smart guy.

Remember to read @GeneWiengarten, @Gloria Horton Young, @Steve Valk and @Heather Cox Richardson on Substack.

My artwork, mugs, and other assorted crap can be found at these fine establishments.

Trevor at FineArtAmerica

Trevor at RedBubble

Trevor at TPublic

Trevor, this made me think that in certain families love doesn’t show up with casseroles or hugs. It shows up as an argument you’re finally allowed to win. Which is thrilling. And terrifying. And, if you’re lucky, unforgettable.

You start with that line about one of you possibly ending up in the morgue, and it’s so blunt it feels almost polite. No warming up, no throat-clearing. Just: here are the stakes, let’s proceed like adults. I trusted you immediately.

Your father comes across not as a tyrant or a legend, but as a man whose intelligence walked into rooms ahead of him. The story about the professors hovering over the math problem while a six-year-old solves it quietly is both impressive and a little alarming. The kind of brilliance that doesn’t ask for admiration, it just rearranges the furniture.

So when we arrive at the argument itself, the real one, it doesn’t feel like a win so much as a moment of atmospheric change. That line, the almost casual admission that you’d read more than he had and might be right, is doing an enormous amount of emotional work. In some households that’s nothing. In yours, it’s a standing ovation delivered at conversational volume.

The trichloroethylene “beer” story does what the best family stories do. It makes us laugh, just long enough to realize we probably shouldn’t be laughing, and then leaves us sitting there with that realization. You have excellent timing.

The Pont du Gard, the olive tree, the ashes, feels less symbolic than sensible. Of course you put him somewhere ancient and sturdy. Some stories need architecture.

This isn’t really about winning an argument. It’s about being seen, briefly and unmistakably, by someone who didn’t offer that lightly. For anyone raised on intelligence as affection and restraint as love, this reads like recognition. And for the record, the score was never Dad 11,679, You 0. It was Dad 11,679, You 1. And that one mattered more than it looked at the time.

Hate to break it to you (actually, if I'm honest --- perversely delighted...) that you and dear departed dad are very much alike in the matter of grey matter. Artists and physicists/mathematicians share comparable, interconnected mental abilities. You both seek to understand and represent the world using different tools, but deeply related cognitive tools --- and an ingrained ability to piss each other off.